Scaling a Kafka consumer group with Kubernetes operator and HPA

Kubernetes (k8s) has introduced a number of ways to extend its APIs and data structure for customising and managing complex workloads. In this post, I attempt to leverage k8s’s Operator pattern and Custom Resource Definition (CRD) to manage the life cycle of a Kafka consumer group running atop a k8s cluster.

Table of Contents

Source code with instruction for this post: https://github.com/thanhnamit/kconsumer-group-operator

Competing consumers pattern in K8S

Competing consumers pattern is the basic messaging pattern that allows a group of consumers to read messages from a group of channels (topics or queues) in parallel style. This pattern fits for real-time streaming scenarios. For example, consuming IoT events as fast as possible from a message broker then persisting events in a database when the order of messages is not important.

When running Kafka consumers in k8s, each consumer is deployed as a replica (pod) and scaled to consume more messages. Although the consumers are stateless, a Kafka consumer group has its state depending on number of partitions available for a topic. To scale appropriately, an engineer needs to understand the Kafka’s scaling approach:

- A Kafka topic contains multiple partitions.

- Kafka manages the group of consumers cooperatively, it knows how many consumer instances are available and dynamically assigns partitions to consumers. Multiple assigning strategies can be applied (Range, RoundRobin, Custom..), RoundRobin is used to make sure no consumer is idle.

- Kafka assigns 1 partition to 1 consumer, and 1 consumer can listen to multiple partitions. So a rule of thumb is if we have n topics with m partition each, we can scale to n * m replicas for maximising parallelism.

- Important Kafka consumer metrics are records-lag-max, fetch-rate, records-consumed-rate, bytes-consumed-rate.

- Kafka consumers work in a group. For any change to the group such as adding, removing, or restart, the broker rebalances its assigned partitions; the rebalancing temporarily stops the consumption activity.

The

record-lag metric and number of partitions per topic are dynamic values that can be changed anytime in production environment. For example, when a Kafka cluster adds a new broker node, changes number of partitions of an existing topic, or producers emit a large volume of messages to the platform. To test how Kafka scaling behaves based on these values, I prototyped

Spring boot Kafka apps with spring actuator and micrometer-registry-prometheus to expose http endpoints for Prometheus to scrape Kafka metrics.

For the single-threaded consumer, I added artificial delay of 10 miliseconds to simulate the actual work has to be done on the received message, so the throughput of this listener is about 100 tps. The kakfa consumer config also explicitly added to control default settings:

spring:

kafka:

consumer:

enable-auto-commit: true

group-id: "kconsumer-grp"

client-id: "kconsumer-app"

bootstrap-servers: my-cluster-kafka-bootstrap:9092

key-deserializer: org.apache.kafka.common.serialization.StringDeserializer

value-deserializer: org.apache.kafka.common.serialization.StringDeserializer

properties:

auto.commit.interval.ms: 5000

max.poll.interval.ms: 300000

max.poll.records: 300

session.timeout.ms: 30000

heartbeat.interval.ms: 1000

partition.assignment.strategy: org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.RoundRobinAssignor

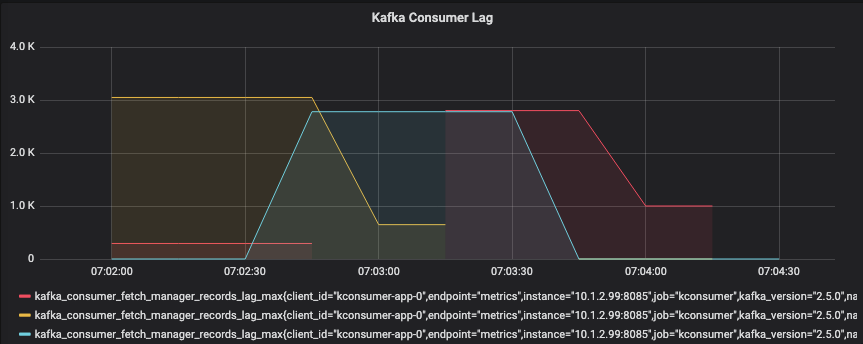

On the producer side, I sent messages to a single topic (3 partitions) without delay, the key is empty so Kafka broker applies DefaultPartitioner and distributes messages to 3 partitions of the topic. This Grafana graph below shows significant lag across all partitions when testing with 10K of messages, 1 consumer. The period of lag per partition is approximately 60 seconds and the whole process takes approximately 180 seconds.

Let’s scale the consumer to 3 replicas and retest:

So scaling reduces lag and provides better responsiveness. We still rely on the manual process here. In production / realtime environment, a significant delay (a gap for Ops team member to react to the alert) is not acceptable and violate SLO (service level objective). In the next section and the rest of this post, I will focus on the Operator pattern as an abstraction for centralising operational knowledge. The goals for the operator are:

- Deploy Kafka consumers and accompanying monitoring, alert rules.

- Deploy HorizontalPodAutoscaler (HPA) to automatically scale consumers based on Kafka metrics.

- Detect if the number of partitions changed and update HPA’s specification.

Kubernetes operator overview

Since the introduction of Operator by Coreos in 2016, the pattern has been applied widely to manage complex cloud-native applications. Community operators are available on Operator Hub allows SREs to speed up installations on Kubernetes or Openshift. Additionally, Coreos and Red Hat have created Operator SDK that streamlines operator development with Golang, Helm and Ansible. Operators can automate a range of Day 1 and Day 2 tasks on behalf of SREs such as basic install, upgrades or workload scheduling and autoscaling. Operator maturity model has provided details for those capabilities.

Build a Golang-based operator

Prerequisite: In this demonstration, I reuse Strimzi operator for Kafka installation, Topic management and Prometheus operator for monitoring (click here for more details).

Any programming language that can talk to Kubernetes APIs can be used to write operators (i.e Fabric8 for JVM), best available tools are Kubebuilder and Operator SDK by Red Hat. Operator SDK supports Go, Helm or Ansible depending on use cases. Go has huge advantages because it is used to create Kubernetes and its simplicity makes infrastructure/network code more readable, maintainable and performant. Another sweet spot is the ability to directly import resources, types, interfaces from external Go projects or operators as dependencies.

The steps to implement an operator can be broken into:

- Define primary resources

- Define child resources

- Register watches

- Implement Reconciliation logic

- Unit tests and e2e tests

- Build operator image, register CRD to Kubernetes

- Deploy and test

Primary resource

To design an operator, we start with the data structure of CRD. Following yaml file describe the structure we expect the operator to manage:

apiVersion: thenextapps.com/v1alpha1

kind: KconsumerGroup

metadata:

name: kconsumer

namespace: default

spec:

averageRecordsLagLimit: 1000

consumerSpec:

containerName: kconsumer

image: thenextapps/kconsumer:latest

topic: fast-data-topic

minReplicas: 1

status:

activePods:

- kconsumer-6c5f87c746-ltrk5

message: "Message: Reconciliation completed, Error: <nil>"

replicas: 1

The new CRD KconsumerGroup is a Primary Resource and its spec describes the individual consumer specification such as consumer name,

image, the topic it should poll messages from, minReplicas indicates the minimum number of consumers to start with, averageRecordsLagLimit set the threshold for HPA to scale out. In term of status, we want to see active pods and a customised message.

The structure above can be expressed as Golang struct types as below:

type KconsumerGroup struct {

metav1.TypeMeta `json:",inline"`

metav1.ObjectMeta `json:"metadata,omitempty"`

Spec KconsumerGroupSpec `json:"spec,omitempty"`

Status KconsumerGroupStatus `json:"status,omitempty"`

}

// KconsumerGroupSpec defines the desired state of KconsumerGroup

type KconsumerGroupSpec struct {

MinReplicas int32 `json:"minReplicas"`

AverageRecordsLagLimit int32 `json:"averageRecordsLagLimit"`

ConsumerSpec ConsumerSpec `json:"consumerSpec"`

}

// ConsumerSpec defines the consumer's attributes

type ConsumerSpec struct {

PodName string `json:"containerName"`

Image string `json:"image"`

Topic string `json:"topic"`

}

// KconsumerGroupStatus defines the observed state of KconsumerGroup

type KconsumerGroupStatus struct {

Message string `json:"message"`

Replicas int32 `json:"replicas"`

ActivePods []string `json:"activePods"`

}

Child resources

A primary resource often has child resources associated with, these resources are native Kubernetes or belong to 3rd party vendor. In this example I want to reuse:

Kubernetes native resources:

- Deployment

- Service

- HorizontalPodAutoscaler

Vendor resources:

- KafkaTopic (Strimzi operator)

- ServiceMonitor (Prometheus operator)

- PrometheusRule (Prometheus operator)

The next step is to create a controller to host the core logic of the operator. The controller does the following things:

- Register watches - operators need to know what resources it monitors

- Execute reconciliation loops - reconcile the resource states

Register watches

...

// Create a new controller

c, err := controller.New(controllerName, mgr, controller.Options{Reconciler: r})

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Watch for changes to primary resource KconsumerGroup

err = c.Watch(&source.Kind{Type: &thenextappsv1alpha1.KconsumerGroup{}}, &handler.EnqueueRequestForObject{})

if err != nil {

return err

}

....

// Watch for changes to KafkaTopic (not created by kconsumer)

u := &unstructured.Unstructured{}

u.SetGroupVersionKind(schema.GroupVersionKind{

Kind: "KafkaTopic",

Group: "kafka.strimzi.io",

Version: "v1beta1",

})

u.SetName(kafkaTopic)

err = c.Watch(&source.Kind{Type: u}, &handler.EnqueueRequestForObject{})

if err != nil {

return err

}

Note we also want to watch for changes from KafkaTopic resource, which is CRD created by Strimzi operator. This sharing knowledge enables operators to cooporate on resource changes effectively.

Reconcile loop

Upon receiving a request (an event triggered by Kubernetes for a change happened a resource). The reconcile loop is the place to implement the changes to the child resources managed by the operator. In this case we want to update HorizontalPodScaler spec when a kafka topic’s partition count is updated.

func (r *ReconcileKconsumerGroup) Reconcile(request reconcile.Request) (reconcile.Result, error) {

reqLogger := log.WithValues("Request.Namespace", request.Namespace, "Request.Name", request.Name)

reqLogger.Info("Reconciling KconsumerGroup")

// Primary resource

kgrp := &thenextappsv1alpha1.KconsumerGroup{}

err := r.client.Get(context.TODO(), types.NamespacedName{

Namespace: request.Namespace,

Name: consumerName,

}, kgrp)

if err != nil {

if errors.IsNotFound(err) {

return reconcile.Result{}, nil

}

return reconcile.Result{}, err

}

....

// Manage Kafka topic changes

reconcileResult, err = r.reconcileTopicChange(kgrp, request)

if err != nil {

reqLogger.Error(err, "Error reconciling topic")

r.updateStatus(kgrp, "Error reconciling Kconsumer group for topic changes", false, err)

return *reconcileResult, err

} else if err == nil && reconcileResult != nil {

reqLogger.Info("Reconciled topic changes")

return *reconcileResult, nil

}

}

The reconcileTopicChange(kgrp, request) method will inspect KafkaTopic’s change, and then update HPA’s maxReplicas

with number of partitions

func (r *ReconcileKconsumerGroup) reconcileTopicChange(kgrp *thenextappsv1alpha1.KconsumerGroup, request reconcile.Request) (*reconcile.Result, error) {

if request.Name != kafkaTopic {

return nil, nil

}

log.Info("Reconciling HPA topic changes")

return r.reconcileHPA(kgrp)

}

func (r *ReconcileKconsumerGroup) reconcileHPA(kgrp *thenextappsv1alpha1.KconsumerGroup) (*reconcile.Result, error) {

hpa := &autoscaling.HorizontalPodAutoscaler{}

err := r.getObj(kgrp, hpa)

if err != nil && errors.IsNotFound(err) {

log.Info("Creating Kconsumer HPA")

hpa, err := r.createHPA(kgrp)

err = r.createObj(hpa)

return r.handleCreationResult("Errors creating Kconsumer HPA", err)

} else if err != nil {

return r.handleFetchingErr("Failed to get Kconsumer HPA", err)

} else {

updateRequired, err := r.updateHPA(kgrp, hpa)

if updateRequired {

log.Info("Updating Kconsumer HPA")

err = r.updateObj(hpa)

return r.handleUpdateResult("Failed to update Kconsumer HPA", err)

}

return nil, nil

}

}

func (r *ReconcileKconsumerGroup) createHPA(kgrp *thenextappsv1alpha1.KconsumerGroup) (*autoscaling.HorizontalPodAutoscaler, error) {

partitions, _ := r.getTopicPartition(kgrp)

var limit string

limit = strconv.Itoa(int(kgrp.Spec.AverageRecordsLagLimit))

hpa := &autoscaling.HorizontalPodAutoscaler{

ObjectMeta: metav1.ObjectMeta{

Name: kgrp.Name,

Namespace: kgrp.Namespace,

},

Spec: autoscaling.HorizontalPodAutoscalerSpec{

ScaleTargetRef: autoscaling.CrossVersionObjectReference{

Kind: "Deployment",

Name: kgrp.Name,

APIVersion: "apps/v1",

},

MinReplicas: &kgrp.Spec.MinReplicas,

MaxReplicas: int32(partitions),

Metrics: []autoscaling.MetricSpec{

{

Type: autoscaling.PodsMetricSourceType,

Pods: &autoscaling.PodsMetricSource{

MetricName: "kafka_consumer_fetch_manager_records_lag_max",

TargetAverageValue: resource.MustParse(limit),

},

},

},

},

}

return hpa, r.setOwnerReference(kgrp, hpa)

}

Run unit / e2e tests

Run unit test:

go test -timeout 30s github.com/thanhnamit/kconsumer-group-operator/pkg/controller/kconsumergroup -run TestKconsumerGroupController

E2E test requires the environment is ready. Once installed Kubernetes, Prometheus and Strimzi operators, you can excute:

operator-sdk test local ./test/e2e --operator-namespace default

Build images

To update vendor libraries, build the image and push to container registry

go mod vendor

operator-sdk build thenextapps/kconsumer-group-operator:v0.0.1

docker push thenextapps/kconsumer-group-operator:v0.0.1

With the image version ready, you need update the operator image name and version at deploy/operator.yaml

Deploy and test

First we deploy a Kafka topic with 01 partition and 01 producer

kubectl create -f apps/k8s/create-kafka-topic.yaml

kubectl wait KafkaTopic/fast-data-topic --for=condition=Ready --timeout=300s

kubectl create -f apps/k8s/kproducer-deployment.yaml

In this step, we will deploy the generated CRD definition. The SDK also generates manifests (service account, role and role binding) for Kubernetes to manage the access, modify these files to fit your security requirement.

kubectl create -f deploy/crds/thenextapps.com_kconsumergroups_crd.yaml

kubectl create -f deploy/service_account.yaml

kubectl create -f deploy/role.yaml

kubectl create -f deploy/role_binding.yaml

kubectl create -f deploy/operator.yaml

Once Operator is up and running, we can create the primary resource. The operator will initialise the process of creating all child resources.

kubectl create -f deploy/crds/thenextapps.com_v1alpha1_kconsumergroup_cr.yaml

kubectl get KconsumerGroup kconsumer -o yaml

To verify all resources are available with commands:

kubectl get HorizontalPodAutoscaler kconsumer -o yaml

kubectl get ServiceMonitor kconsumer -o yaml

kubectl get PrometheusRule kconsumer -o yaml

kubectl get service kconsumer -o yaml

kubectl get deployment kconsumer -o yaml

The final state of the default namespace should look like:

kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

kconsumer-6c5f87c746-ptsbg 1/1 Running 0 20h

kconsumer-group-operator-7db8f9b8c8-whh5p 1/1 Running 0 158m

kproducer-58b7bb7d66-bzlwg 1/1 Running 0 26h

my-cluster-entity-operator-68b7df59b9-bvtx2 3/3 Running 2 26h

my-cluster-kafka-0 2/2 Running 0 26h

my-cluster-zookeeper-0 1/1 Running 0 26h

strimzi-cluster-operator-6c9d899778-fhdlt 1/1 Running 1 26h

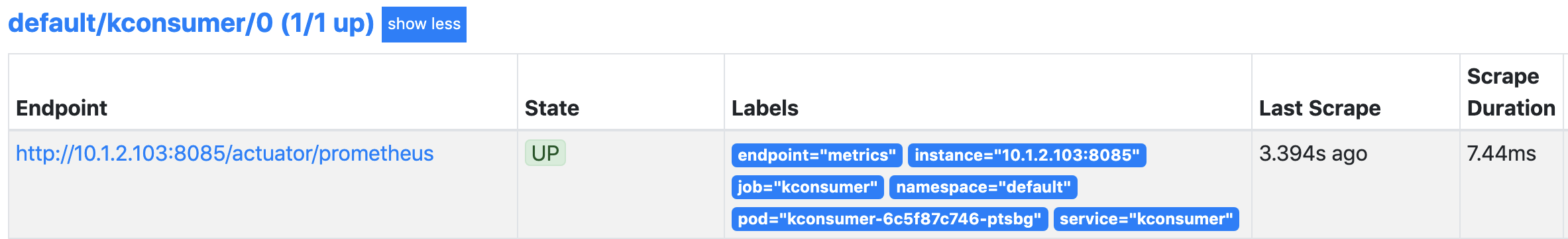

Using kubectl port forwarding, you can verify at http://localhost:9090/targets to check metric scraping status:

kubectl --namespace monitoring port-forward svc/prometheus-k8s 9090

Now Kafka metrics are available and ready to be viewed in Prometheus/Grafana, let’s do few more tests to see if the operator

fulfil the design goals. First, we change the KafkaTopic’s partition from 1 to 3, we expect the operator to update

HPA’s maxReplicas to 3. Update the file create-kafka-topics.yaml and set partitions: 3 then run:

kubectl apply -f k8s/create-kafka-topics.yaml

kubectl wait KafkaTopic/fast-data-topic --for=condition=Ready --timeout=300s

kubectl get HorizontalPodAutoscaler kconsumer -o yaml

HPA spec and status is updated:

...

spec:

maxReplicas: 3

minReplicas: 1

scaleTargetRef:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

name: kconsumer

status:

currentReplicas: 1

desiredReplicas: 1

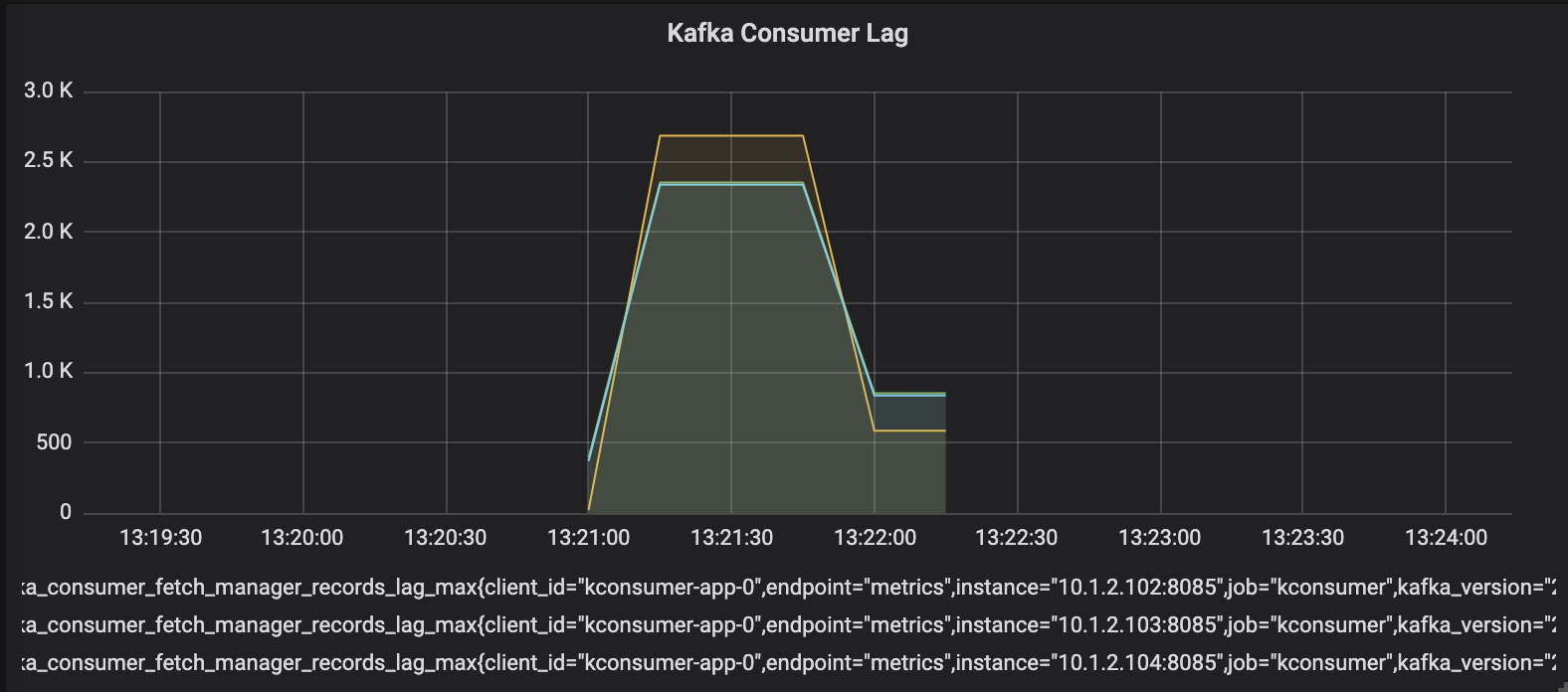

Finally, we test our expectation that the HPA should scale the consumer to 3 pods if the records lag reach averageRecordsLagLimit. This command sends 10K of messages:

curl http://localhost:8083/send/10000

Watch for HPA in action, it scales to 3 pods to serve the demand and few minutes later scale back the consumer to 1 pod.

+ kubectl get hpa -w

NAME REFERENCE TARGETS MINPODS MAXPODS REPLICAS AGE

kconsumer Deployment/kconsumer 0/1k 1 3 1 53s

kconsumer Deployment/kconsumer 3412/1k 1 3 1 107s

kconsumer Deployment/kconsumer 3412/1k 1 3 3 2m1s

kconsumer Deployment/kconsumer 2198333m/1k 1 3 3 2m17s

kconsumer Deployment/kconsumer 1061/1k 1 3 3 2m32s

kconsumer Deployment/kconsumer 0/1k 1 3 3 3m18s

kconsumer Deployment/kconsumer 0/1k 1 3 3 7m24s

kconsumer Deployment/kconsumer 0/1k 1 3 3 8m10s

kconsumer Deployment/kconsumer 0/1k 1 3 1 8m25s

Cleanup

To clean up all resources created by the operator, you just need to remove the primary resource. Kubernetes will automatically take care of this activity.

kubectl delete KconsumerGroup kconsumer

Points for consideration & improvement

- Kafka’s partition rebalancing can impact the overall throughput of the system.

- Running operator does require extra resources of the cluster (they are pods).

- Need to measure the performance impact on Kubernetes APIs.

- Need to tighten security and high availability are also important factors.

- Expose the operator’s metrics to Prometheus so SREs can track operator health & activities.

- Integrate with Operator Lifecycle Manager

Final thoughts

The main benefit of this pattern is that it has potentials to close the gaps that stop business to achieve true resiliency their platform. It is one step toward fully autonomous software in cloud-native environment. The operational knowledge as code can be tracked, versioned and updated just like application code.

When to use an operator? Not all types of workload require writing operators. For most of the scenarios, Kubernetes’s native resources are sufficient. The complexity level of the application, development cost and team capability are sensible factors to justify the decision.

Who should write operators? It is tempting to say this should be done by operating team alone. In fact, operating software is rather complicated, the knowledge acquired to operate software can span across multiple disciplines such as designing, architecting, coding and testing. It should be well-thought-out during the design phase and it is the joined effort among teams. Intuitively, operators can be implemented by developers or SRE team, the engineer should collaborate with architects to understand the quality attributes (non-functional goals) of the platform, also work with SREs to assess infrastructure impact.

Thanks for reading, I would love to hear your feedback and experience with Kubernetes and operator.

Tools of the trade

- kube-prometheus: a community-driven monitoring stack for k8s

- prometheus-adapter: export metrics from Prometheus to Kube’s metric-server

- strimzi-operator: operators to manage Kafka cluster, topics and users in Kubernetes

- operator-sdk: operator sdk

- go-lang

- skaffold: automate some tedious tasks

- jib: containerise spring boot app

References:

- openshift

- monitoring kafka

- K8S: great document for k8s programmer

- kubebuilder: everything about k8s programming

- horizontal pod autoscaler